I know it’s a bootleg, but I was there at that concert, so I ought to have some right to listen to it again… shouldn’t I?

It was August 1978. The location was Penn’s Landing, a strip of park along the Delaware River waterfront in Philadelphia that the city had just rehabilitated for the American Bicentennial. It was a free outdoor concert sponsored — and broadcast live — by WIOQ, one of Philly’s three-count-em-three progressive FM radio stations at the time. The band was a British progressive rock supergroup called U.K.

U.K.’s eponymous debut album from earlier that year had been promoted heavily on the radio with ads featuring a Mahsterpiece Theatre-esque British voice saying, “Collectively, Eddie Jobson, John Wetton, Bill Bruford and Allan Holdsworth have played in some of the world’s greatest rock bands. Bands like King Crimson, Uriah Heep, Yes, Genesis, Roxy Music, and Soft Machine.” The track “In the Dead of Night,” from that album, was in the background of the ad and getting serious radio airplay. It was a spiffy prog-rock tune in 7/4 time featuring Wetton’s vocals, Jobson’s atmospheric synths, Bruford’s crisp drumming, and Holdsworth’s liquid-lightning guitar.

I was a high school junior and getting into prog-rock. But all I knew of those musicians was that Bill Bruford was the original drummer in Yes who played on tracks like “Roundabout” and “Starship Trooper.” I wasn’t sure whether Eddie Jobson’s last name was pronounced “job” as in “work” or “Job” as in the Biblical figure. I had never even heard of Soft Machine.

But I liked “In the Dead of Night.” So when a group of my friends — including a girl I had a crush on — wanted to go see them at Penn’s Landing, I was in.

I remember enjoying the concert — not that I could hear or see much, sitting on a blanket about 300 yards from the stage. I heard a WIOQ DJ introduce the band, intoning the members’ names just like on the radio ad (sans British accent). By that time, I had come to know the debut album, but I didn’t recognize much of the music they played. I knew that Eddie Jobson played violin, and I remember hearing a violin solo. “In the Dead of Night” was the band’s set-closer, before they came back for encores that I didn’t know either.

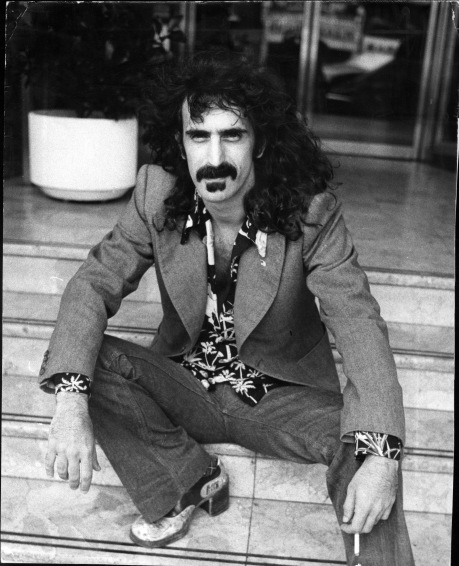

Fast forward a few years to my days in college radio and my deep dive into progressive rock and fusion. I played guitar (badly), and Allan Holdsworth had become one of my idols. Bill Bruford was my hands-down all-time favorite drummer. I bought every album I could find that either of them played on — which was a lot of albums by a lot of different artists. I even interviewed both of them for the radio station when they came into town for gigs. I discovered the great King Crimson lineup of 1972-74 with Wetton and Bruford. I learned that Jobson had played on Roxy Music’s best-known records after Brian Eno left the band, as well as with Frank Zappa, and that Soft Machine was originally part of the 1960s British psychedelic scene alongside Pink Floyd.

In short, U.K. had become much more important to me than it was in August 1978. I had come to regard U.K.’s debut album as a solid entry in the prog canon that represented the state of the art in 1978 rather than some restatement of past glories. Besides “In the Dead of Night,” highlights of the album include Jobson’s “Presto Vivace,” a high-speed, rhythmically complex instrumental interlude that he wrote while on tour with Zappa, which sounds like Zappa with a British stiff upper lip; and Holdsworth’s pensive, elegiac “Nevermore.”

The band’s second album, Danger Money, was recorded after Bruford and Holdsworth had left the band. The new drummer was Terry Bozzio, an American whom Jobson brought in from Zappa’s band; he was a technically dazzling drummer with a wild style that got straightjacketed in the confines of U.K.’s heavily arranged prog. Holdsworth wasn’t replaced; the new lineup was an ELP-style trio with no guitarist. The album was less progressive, more monochromatic, and generally not up to the level of the debut. The trio toured as opening act for Jethro Tull and released a live album from that tour, Night After Night.

U.K. split up in 1979. The band represented a moment in time in the history of prog-rock: the end of its glory period in the 1970s before it had transmuted into fully commercial arena-rock and punk had moved in. By then, King Crimson had broken up, Yes was breaking up, Genesis had sold out, and ELP broke up after attempting to sell out.

Like many supergroups, UK fell apart because its members had different ideas about music that had been formed over years of experience. John Wetton was a powerful, gutsy bass player who did the singing in King Crimson; he was focusing on vocals and wanting to be a rock star. Holdsworth had no use for arena rock and wanted to play jazz fusion. Bruford’s drumming style — which he had honed to perfection by 1978 — was utterly distinctive but also tended towards jazz. And Jobson wanted to play spacy prog.

The musicians’ post-U.K. career paths bore this out. Bruford continued on his previous path as a bandleader with Holdsworth and keyboardist Dave Stewart. The Bruford band’s sophisticated Euro-fusion sound resembled that of National Health, a band associated with Britain’s Canterbury Scene that Bruford and Stewart co-founded after Crimson broke up. Subsequently, Bruford rejoined Robert Fripp in a rejuvenated King Crimson and did copious journeyman work on the fringes of rock, jazz, and avant-garde music while continuously evolving his style.

Holdsworth became a guitar God who would grace the cover of many guitar magazines and influence a generation of fusion and metal shredders — including Eddie Van Halen, who produced one of his solo albums.

John Wetton, meanwhile, made his dreams of pop stardom come true. He formed and fronted the mutant arena-schlock-rock band Asia with Yes-men Steve Howe and Geoff Downes, and Carl Palmer from ELP. Asia lasted longer than U.K., the members being united in a common desire to get rich. Asia got several singles into the charts. Jobson briefly joined Jethro Tull, then settled into a low-key career of producing, film and TV scoring, and occasional solo albums.

Both Wetton and Holdsworth sadly passed away last year. That prompted Jordan Becker, my college radio comrade-in-arms who accompanied me to many a Crimson and Holdsworth gig, to write a blog post commemorating the many influential guitarists who died in 2017. This in turn led me to discover the existence of digital files of the tapes of the radio broadcast of that August 1978 U.K. concert in Philly.

What an amazing experience it was to listen to that gig forty years later, armed with all the knowledge and context I had gained since then. The tunes I hadn’t recognized that night turned out to be a mixture of songs from the then-forthcoming Danger Money and Bruford’s One of a Kind solo album. The Danger Money tunes had different dimensions with Holdsworth on guitar and Bruford’s more distinctive drumming style. The two tunes from One of a Kind (“The Sahara of Snow” and “Forever Until Sunday”) got more aggressive rock treatments from Wetton’s bass and Jobson’s brasher keyboards, compared to the more cerebral approach of the Bruford band.

Allan Holdsworth was supposedly fired from U.K. right after that night’s gig. The reason was the cliche “artistic differences”; but it’s not difficult to hear the evidence from the tapes. While Wetton and Jobson were playing blockbuster ELP-style prog-rock for the crowd, Holdsworth was playing fluid, jazzy, saxophone-like lines on guitar, eschewing power chords for abstruse scales and harmonies, improvising all over the place, and generally playing music more befitting a small club than a big outdoor gig. Wetton and Jobson had wanted Holdsworth to reproduce the solos from the album live, but doing that just wasn’t in his blood. The tour, and that edition of the band, ended after the subsequent night’s performance in Cleveland.

The Philadelphia concert is one of a handful of dates from U.K.’s 1978 tour that were broadcast and recorded; the Cleveland, Boston, and Toronto gigs are also available. For fans of these musicians, they’re great documents of their styles in transition as well as suggestions of what might have been. (Speaking of which: that girl ended up as my senior prom date, but nothing else ever happened.)

And by the way: it’s not a bootleg after all. It’s available as one disc of a massive 14-CD, 4 Blu-ray box set called Ultimate Collector’s Edition, if you’re prepared to shell out around $400 for it.